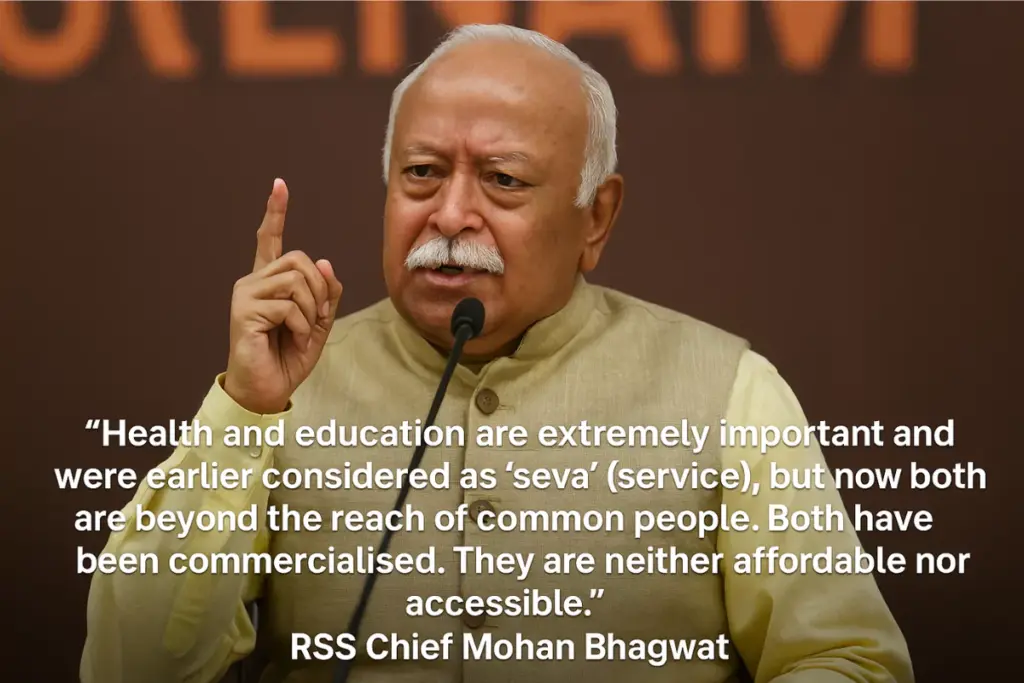

| “…..Health and education are the two subjects that have become a great need for society across the globe. We call today’s times the age of learning. When you want to learn something, your body is the way to it. So, you cannot become intelligent unless you have a healthy body…a person can sell his home to get his children the best education…he will also sell his home to get the best healthcare for himself. Ironically, both these important things are now out of the reach of common people,” RSS supremo Mohan Bhagwat said. |

Education and Healthcare: The Two Pillars of Life

We all know that two things matter the most in life, health and education. Without good health, nothing else feels important, and without education, progress becomes difficult. Recently, RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat made a strong point: families are ready to sell their homes if needed, just to get the best schooling for their children or the right treatment for their loved ones.

That shows how deeply these two needs touch every family.

But here’s the problem: both education and healthcare have slowly become too expensive.

What used to be about serving people, teaching children or treating patients, now looks more like a business. Parents are crushed under high school and college fees, while hospital bills can wipe out a family’s savings in days. This change is something we all see and feel around us.

As a result, quality education and good health have slipped out of reach for a large section of society.

In this opinion article, we explore how this trend unfolded and why it is a cause for serious concern.

| Note: This is an opinion article and is the author’s personal view. It is a small contribution to the debate on Education and Healthcare started by RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat. |

Education and Healthcare: From Service to Business

Not long ago, running a school or a hospital was considered an act of service in India, a way to give back to society.

As RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat recently reminded us, “good health and education used to be considered a service” in our tradition. Teachers and doctors were revered for their dedication.

Bhagwat noted that a minister once described Indian education as a “trillion-dollar business,” highlighting how lucrative, and thus how expensive, it has become. The endless drive for profit in the name of “quality” has made decent schools and hospitals unaffordable and inaccessible to the common citizen. What was earlier done as a duty or charity is now done for a hefty fee.

In Bhagwat’s words, “everyone needs education and healthcare, but both are now beyond the common man’s financial ability because they have been commercialised”.

| This raises a Question: What prompted Shri Mohan Bhagwat to make such a statement? RSS Chief Shri Mohan, speaking in Indore, also pointed out that the number of hospitals and schools is increasing rapidly. However, their services are so costly that the common man cannot access them. Everyone knows that the present government has close links with the RSS. Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi himself was once an RSS pracharak, and even today, many RSS leaders are part of the BJP-led government. |

This shift from a service mindset to a business mindset means that decisions are made for maximising revenue rather than public welfare. As a consequence, students and patients are treated less like beneficiaries and more like paying customers.

This commercialisation has also led to the centralisation of facilities.

Corporate-style growth means large private hospital chains and elite school franchises concentrate in big cities, forcing people to travel far for good services.

Bhagwat pointed out that when people must travel long distances for treatment or study, they incur extra costs for travel and stay expenses that hit middle-class and poor families hard. It’s a double blow: the service itself is costly, and accessing it adds more cost.

The irony is painful, India traditionally upheld health and education as part of “dharma” (social responsibility), but now they are treated as commodities.

Bhagwat contrasted the Western idea of “survival of the fittest” with India’s philosophy, where the strong uplift the weak. He appealed to revive the spirit of “Lok Kalyan” (public welfare) rooted in our culture rather than merely ticking the box of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

In simpler terms, he called for treating education and healthcare as shared social duties again, not just markets to make money. This back-to-basics message is a wake-up call to our leaders and society.

Families Burdened by Medical Expenses

Nowhere is the pain of profiteering felt more viscerally than in healthcare. Medical emergencies, which should find families focused on healing, instead find them worrying about money.

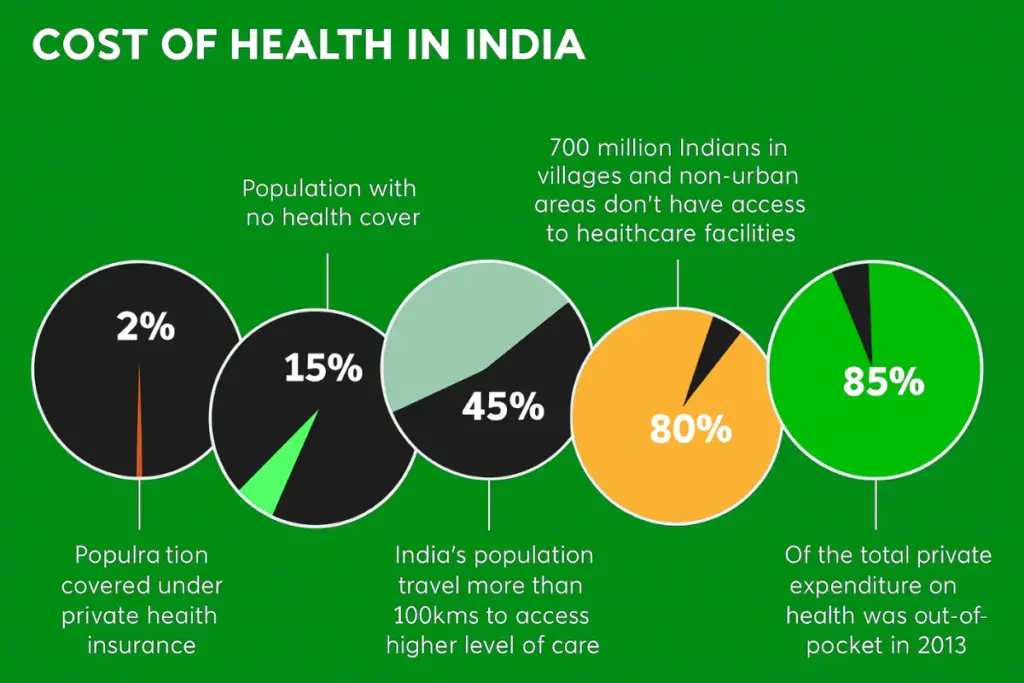

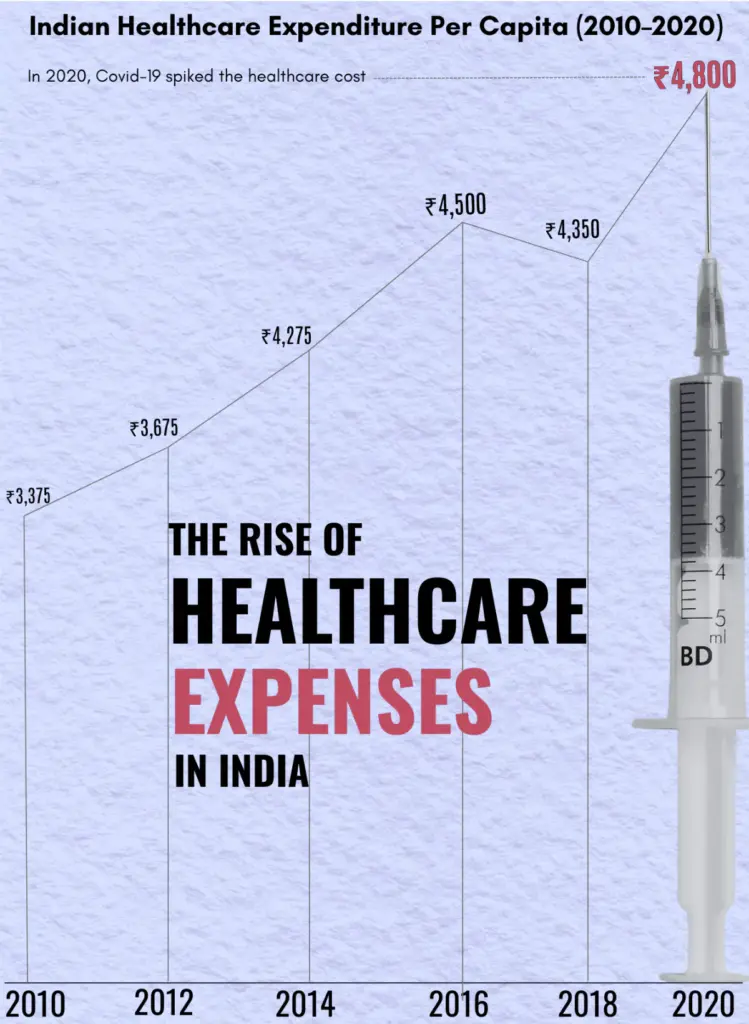

India has one of the highest out-of-pocket medical expenditures in the world, meaning most people pay for health services from their own pockets rather than through insurance or government support.

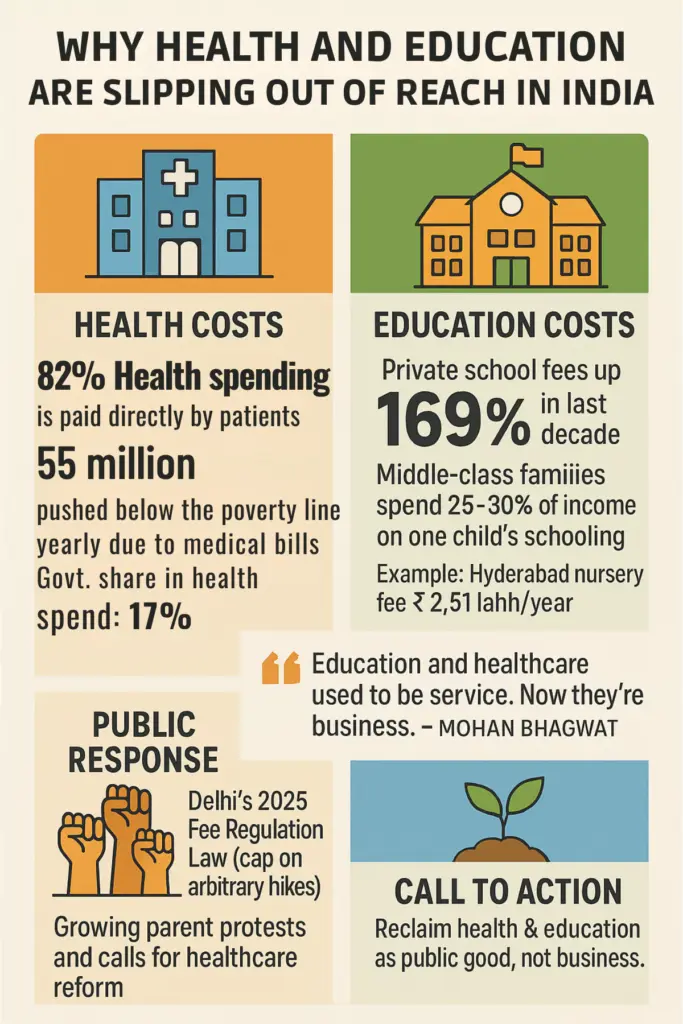

Only about 17% of total health spending in India is covered by the government, leaving an astonishing 82% to be paid by patients themselves.

In other words, the government bears barely a sixth of healthcare costs, while ordinary citizens shoulder the rest, often through “hardship financing” like loans or selling assets.

The result? Each year, millions of families are pushed into poverty due to medical bills.

A World Health Organisation report found that over 55 million Indians are forced below the poverty line annually because of healthcare expenses. Many end up in lifelong debt; others forego treatment altogether, risking their lives.

It’s bitterly ironic that India is called the “pharmacy of the world” (for manufacturing affordable medicines) yet 65% or more of health spending by Indians is out-of-pocket on things like medicines and consultations.

Despite economic growth, our public health funding remains abysmally low (around 1-1.5% of GDP), leading to under-resourced government hospitals and a mushrooming of private clinics. These private hospitals often charge exorbitant rates in the absence of strong regulation.

The extreme desire for profit can even lead to unethical practices, unnecessary tests, inflated bills, or a preference to treat only well-off patients who can pay.

Meanwhile, a large portion of India’s disease burden now comes from chronic non-communicable diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Managing these conditions requires regular tests, lifelong medications, and specialist care, which can drain a family’s savings.

Health insurance coverage is still limited and often inadequate; most plans do not fully cover outpatient consultations or expensive drugs. So even insured middle-class families find themselves paying huge sums that insurance won’t reimburse.

The financial stress from healthcare is not just a statistic; it’s a daily reality for many. There are heartbreaking stories of people selling land or jewellery for a relative’s cancer treatment, or skipping proper treatment because they fear the costs.

When a family member falls seriously ill, the family often faces a cruel dilemma: incur massive debt or risk the loved one’s life.

These are choices no one should have to make.

Access to healthcare is literally a matter of life and death, and our society cannot afford to leave it to the mercy of the market.

We must remember that healthcare is not a luxury item; it is a fundamental human need. Ensuring affordable medical care for all citizens is a basic duty of any humane society, and India cannot claim to be a truly developed nation until it lightens this crushing medical cost burden on its people.

The Soaring Cost of “Quality” Education

Parallel to the healthcare crisis is an education affordability crisis. The places we once called “temples of learning” have increasingly become centers of commerce.

Private schools that promise “quality education” charge fees that can make any parent’s head spin. Across cities and even smaller towns, school fees have surged well beyond inflation and income growth.

A national survey in 2024 revealed that private school fees in urban India jumped 169% in the last decade, far outpacing average salary increases.

It’s not unusual now for a middle-class family in a metro city to spend anywhere between ₹1.5 lakh to ₹5 lakh ($1,800–$6,000) per year, per child on schooling costs. This includes not just tuition, but also a host of “extras”: transportation, uniforms, textbooks, activity fees, building funds, and so on.

Such expenses were unheard of a generation ago. Many parents today feel the pinch so badly that they jokingly (or not so jokingly) say one parent’s salary is dedicated entirely to paying school fees. This is not an exaggeration; dual-income couples often find that by the time they pay the school’s demands, there’s little left from one full income.

Private schools have become adept at finding new ways to monetise every aspect of education. Beyond the basic tuition, there are admission fees, “development” fees, building funds, technology fees, and even charges for extracurricular activities or smart classrooms.

Shockingly, some schools require parents to buy books and uniforms only from specific shops (in which the school management has a financial stake), often at marked-up prices. This practice essentially forces parents to overpay for standard items and is a blatant conflict of interest, yet it continues in many places.

For many families, even at average schools, annual schooling costs can exceed ₹60,000 per child, which is a huge share of income for a middle-class household. Some surveys have found families spending over 25-30% of their income on a single child’s education, putting enormous strain on their finances.

Education, which should empower families, is ironically impoverishing them in some cases.

The pursuit of “elite” education has also created a culture where parents feel compelled to pay exorbitant fees in hope of securing their child’s future. But this can reach absurd levels.

Recently, a private school in Hyderabad sparked nationwide outrage when it was revealed they were charging ₹2.51 lakh per year for nursery admission- yes, for a pre-school toddler! This works out to roughly ₹21,000 a month just for a nursery class, an amount that rivals university tuition in some countries.

Read Also: NMC vs Private Colleges on Fee Guidelines 2025: Rising Medical Education Cost Crisis

The fee structure, which went viral online, showed how cleverly it was broken into various components (tuition, initiation fee, deposits, etc.), but the bottom line was clear: a toddler’s education was priced higher than many postgraduate programs.

Parents and the general public were justifiably furious, calling it “extortion” rather than education. Social media was flooded with comments asking how learning the ABCs could possibly cost that much, and pointing out that by law, private schools in India are supposed to be run as non-profit trusts.

The outrage forced the state government to take note; the Telangana government is now considering a regulatory law to cap such fees and bring transparency in private school fee structures. The Hyderabad incident was an extreme example, but it served as a tipping point in the debate on rising education costs.

Public Outrage and Demands for Change

The common people are not taking these developments quietly. Across the country, there is growing outrage and grassroots activism against the blatant profiteering in health and education.

In the education sector, especially, parents’ groups have begun to mobilise. They argue that quality education is a right, not a privilege for the rich.

One notable victory for parents came recently in Delhi. In the 2025 academic year, many private schools in Delhi arbitrarily hiked their fees by 30–45%, burdening parents further. This led to protests at Jantar Mantar. Faced with public pressure, the government had to act.

The Delhi Assembly passed the School Education (Transparency in Fixation and Regulation of Fees) Bill, 2025, a new law to rein in arbitrary fee hikes by private schools. Under this law, schools must now get government approval before raising fees, fully disclose their fee structure, and they face hefty penalties for violations. The intent is to ensure schools cannot increase fees at whim or tack on mysterious charges without oversight.

A similar push is evident in healthcare. While perhaps less organised than the parent protests (since patients are a more transient grouping than school communities), awareness is rising that healthcare needs stronger government intervention and oversight.

Public interest litigations in courts, consumer forum cases against hospitals for overcharging, and social media campaigns highlighting medical bill frauds have all played a role in sparking debate.

Even someone like Mohan Bhagwat issuing a public warning to policymakers is significant, it indicates that concerns about health and education commercialisation have reached the highest levels of public discourse.

Bhagwat’s statement was virtually a call to the government and private sector to introspect and change course. When a leader associated with the ruling establishment (RSS is the ideological parent of the ruling party) says such sectors should not run purely on profit motive, it carries weight.

As he bluntly put it, India needs to view health and education not as markets but as societal obligations, essentially as the rights of every citizen. His appeal to follow moral principles (“Dharma”) for public welfare instead of just corporate tokenism is a message that seems to have struck a chord with many.

It is rare to see consensus across the spectrum on an issue, but on this, many average people, activists, and even political leaders agree: the current model is not working for the masses.

Reclaiming Education and Healthcare as Public Goods

What can be done moving forward?

First and foremost, there needs to be a mindset shift at the policy level – viewing education and healthcare as public goods and fundamental rights, not as commodities to be sold.

This means increasing government investment and involvement in both sectors.

For healthcare, the government must significantly boost public health expenditure (experts suggest to about 2.5% of GDP from the current ~1%) to strengthen government hospitals, provide wider insurance coverage, and subsidise essential treatments.

With better public options, people won’t be forced to rely on expensive private care for every need. It also means enforcing regulations on private hospitals, for example, standardising treatment costs, capping prices of essential drugs and procedures, and insisting on transparent billing.

There should be strict action against malpractices like inflating bills or refusing treatment to those who can’t pay upfront.

Some states have started schemes for cashless treatment of the poor; these should be expanded and effectively implemented.

Ultimately, we should aspire for some form of universal healthcare, where no one is denied treatment for lack of money and no one is impoverished by medical costs.

Policy and Social Responsibility

Achieving that is challenging, but it’s a goal worth working towards if we truly value every life.

In education, the solutions involve both regulation and offering alternatives.

On the regulation side, laws like Delhi’s Fee Regulation Act need to be replicated and enforced in all states, so that private schools are kept in check. It is vital to close loopholes that schools use to dodge rules (such as charging under different heads or demanding “donations”).

At the same time, we must strengthen public education; government schools and colleges should be equipped and improved so they become a viable, quality alternative for middle-class families, not just a safety net for those who can’t afford private schools.

When public schools are excellent, it naturally forces private schools to moderate their greed, because parents have a choice.

The Right to Education (RTE) Act already guarantees free education for economically weaker sections up to a point; we may need to expand such commitments. Perhaps offering more scholarships or support for higher levels, or even exploring a “common school system” where basic education quality is consistent for all.

Additionally, transparency is key, for instance, making private schools publicly declare their financials can remind them that they are technically non-profits and should not be generating huge surpluses on the backs of parents.

Society also has a role.

We need to rekindle the old ethos where doctors and teachers see themselves as a noble profession of service first. This doesn’t mean they should sacrifice a decent livelihood, but rather that profit should not be the primary driver in these fields.

Encouraging more philanthropic and charity-based models, like trusts, NGOs, and religious organisations running affordable schools and hospitals, can help counter the corporate dominance.

In fact, Bhagwat was speaking at the inauguration of an affordable cancer care center run by a charitable trust, showing that such models can work and must be scaled.

Public-private partnerships can also be structured in a way that the “private” isn’t just looking at the bottom line but is held accountable to social objectives.

Mohan Bhagwat’s sharp critique of the marketisation of health and education is a timely reminder of our societal priorities. It shines a light on the painful truth that millions of Indians are one hospital bill or one school admission away from financial ruin. We cannot allow basic needs like healthcare and education to become luxuries.

The government, as the guardian of citizens’ welfare, must take this concern seriously and deliberate on policy overhauls. This might include stricter regulations, greater public funding, and perhaps even constitutional or legal guarantees to protect citizens’ rights in these areas.

Equally, those running educational and medical institutions must introspect about their values, there is a difference between running a sustainable enterprise and exploiting a captive market of desperate patients or anxious parents. The balance has tilted too far towards the latter, and it’s time to course-correct.

Development Must Mean Dignity

India aspires to be a prosperous, developed nation, but true development is measured by the well-being of its people, not just GDP numbers.

An equitable society is one where a family doesn’t have to choose between sending their child to a good school or saving for retirement, and where falling sick doesn’t mean falling into lifelong debt.

To build such a society, education and healthcare must be brought back into the fold of public good with a service ethos. Profit may have its place in innovation and efficiency, but it cannot be the only guiding force for sectors that touch the core of human dignity.

As citizens, we should continue to speak up and demand that our leaders act. The recent voices, from an outraged parent in Hyderabad to the RSS Sarsanghchalak himself, have started a crucial conversation.

Let’s hope this leads to concrete change, so that soon, no child is denied a good education and no person dies untreated simply because they weren’t “wealthy enough.”