Doctor Availability Crisis of India in 2030: India’s healthcare system has seen remarkable expansion over the last seven decades. From only 19 medical colleges at independence, it now have more than 800 medical colleges and over 1.3 lakh MBBS seats. Yet, India continues to lag behind comparable nations, both in Asia and across emerging economies, on basic health indicators such as infant mortality, maternal mortality, life expectancy, and access to skilled birth assistance.

This article presents an analytical, data-rich, and evidence-based examination of India’s doctor production capacity, the real availability of practising doctors, the effects of emigration and retirement, and India’s likely doctor-population ratio by 2030.

India’s Health Indicators: Why Growth Has Not Resulted in Better Outcomes

India’s performance on basic health indicators has not kept pace with countries that have similar economic and demographic profiles. In 2024, India’s healthcare outcomes were significantly lower than those of comparable China, neighbouring Sri Lanka, and all BRICS nations.

Table 1: Basic Health Indicators of Selected Developing Countries (2024-25)

| Country | Life Expectancy (Years) | Infant Mortality (per 1,000 live births) | Maternal Mortality (per 100,000 live births) | Births Attended by Skilled Personnel (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 72.48 | 24.98 | 93 | 89.4% [WHO Report on Healthcare] |

| China | 79 | 4.8 | 23 | 99.9% |

| Top Country | Monaco – 87 | Slovenia – 1.5 | Belarus – 1 | Uruguay – 100% |

Note that all the top countries performing best in health indicators are very small compared to India. But, china is ideally same and more over till 1990, economy size of both India and China were same. But after 1990, chinese policies turned it around and outpaced India many fold.

Doctor Production Capacity: A Historical Review (1947-2015)

India’s medical education system has exploded, but this growth has not been uniform across time.

Table 2: Growth of Medical Colleges in India

| Year | No. of Medical Colleges | % Private |

|---|---|---|

| 1947 | 19 | 0% |

| 1965 | 86 | Minimal |

| 1990 | 143 | 20% |

| 2009 | 287 | 30%+ |

| 2025 | 816 | 47%+ |

Table 3: Doctors Added Annually to the Indian Register

| Year | Newly Registered Doctors |

|---|---|

| 1961 | 4,066 |

| 1991 | 14,023 |

| 2001 | 21,263 |

| 2011 | 33,927 |

| 2014 | 26,342 |

According to the National Medical Commission (NMC), as of July 2024, India has 13,86,136 allopathic doctors registered with State Medical Councils and the NMC.

Table 4: Total Stock of Registered Doctors (Cumulative)

| Year | Registered Doctor Stock |

|---|---|

| 1960 | 75,594 |

| 1990 | 393,424 |

| 2000 | 566,102 |

| 2010 | 824,673 |

| 2014 | 943,529 |

| 2024 | 13,86,136 |

Despite producing nearly one million registered doctors over seven decades, India still faces a critical shortage of practising doctors. The real problem lies in attrition, emigration, and the mismatch between medical training and public health needs.

Why India’s Doctor Numbers is Misleading

Union Health Minister Mansukh Mandaviya told the Rajya Sabha on April 5, 2022 that India has a doctor-population ratio of 1:834, based on 80% availability of registered allopathic doctors and 565,000 AYUSH practitioners.

But this figure is misleading because:

- It counts every doctor ever registered, many of whom are retired or deceased.

- It does not exclude those who have emigrated, shifted professions, or ceased medical practice.

- It does not differentiate between specialists and primary care doctors, although rural India primarily needs general practitioners.

- It also includes AYUSH practitioners.

Adjusted Method: Estimating Active Doctors in India

Researchers use a simple but logical assumption:

- Doctors typically start practicing at age 28-30.

- They retire or significantly reduce work by age 65.

- Therefore, doctors registered 35 years ago should be considered retired.

Using this assumption:

- Registered stock in 2014: 13,86,136 (14 Lakh)

- Doctors registered before 1990 (retired): 3,93,424 (4 Lakh)

- Estimated emigrated doctors: ~1 Lakh

- Active doctors in India (2024): 9 Lakh

Doctor-Population Ratio (Realistic)

- 9 Lakh doctors / 150 Crore people = 6 doctors per 10,000 population.

- This is about 50% lower than the official figure of 12/10,000.

Emigration of Indian Doctors: A Massive Drain on Human Capital

India is among the world’s largest contributors of medical professionals to advanced economies, especially to GCC nations, Europe, and other English-speaking countries.

OECD data on shows that, nearly 69,000 Indian-trained doctors and 56,000 Indian-trained nurses were employed in the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, and Australia.

Although large numbers of Indian health professionals also migrate to Gulf countries, reliable data on their exact strength remains limited, and India still lacks real-time tracking of high-skilled migration, unlike its systems for low- and semi-skilled workers.

Table 5: Indian Doctors Practicing Abroad (2013-14)

| Host Country | No. of Indian Doctors |

|---|---|

| USA | 48,337 |

| UK | 25,116 (23,420 licensed to practice) |

| Australia | 3,981 |

| Canada | 1,943 |

| New Zealand | 468 |

| Germany | 177 |

| Norway | 36 |

| Gulf Countries | ~10,000 (estimated) |

Total Estimated Indian Doctors Abroad: ~1 Lakh. This is 8% of India’s active and highly skill ful doctor workforce, a significant loss.

Read Also: Doctor Shortage in India 2025: Can AI Bridge the Healthcare Gap Before It’s Too Late?

Why India’s Growing Number of Doctors Has Not Improved Healthcare

Despite rapid growth in medical colleges, India’s health indicators remain poor. The reasons:

Reason 1: Population Growth Outpaces Doctor Production

Doctor production increased, but not fast enough to meet the needs of an additional 1 billion people since 1947.

Reason 2: Specialist-Heavy Workforce

Private medical colleges tend to produce more specialists, but rural India needs:

- General practitioners

- Family physicians

- Community medicine experts

- Primary care doctors

This mismatch in training reduces the availability of doctors for frontline care.

Reason 3: Registered Doctors ≠ Active Doctors

The government relies on registration data, which ignores:

- Retirements

- Deaths

- Emigration

- Career shifts

As a result, policy decisions are based on inflated workforce numbers.

Reason 4: Urban-Rural Imbalance

Maharashtra alone holds 14% of registered doctors, while:

- Madhya Pradesh: ~3%

- Rajasthan: ~3%

- Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand: severe shortages

Doctors overwhelmingly prefer urban postings with:

- Better salaries

- Private sector opportunities

- Safer living conditions

- Access to technology and training

Read Also: India’s Public Health System Fails the Poor: Study Highlights Urban-Rural Gaps

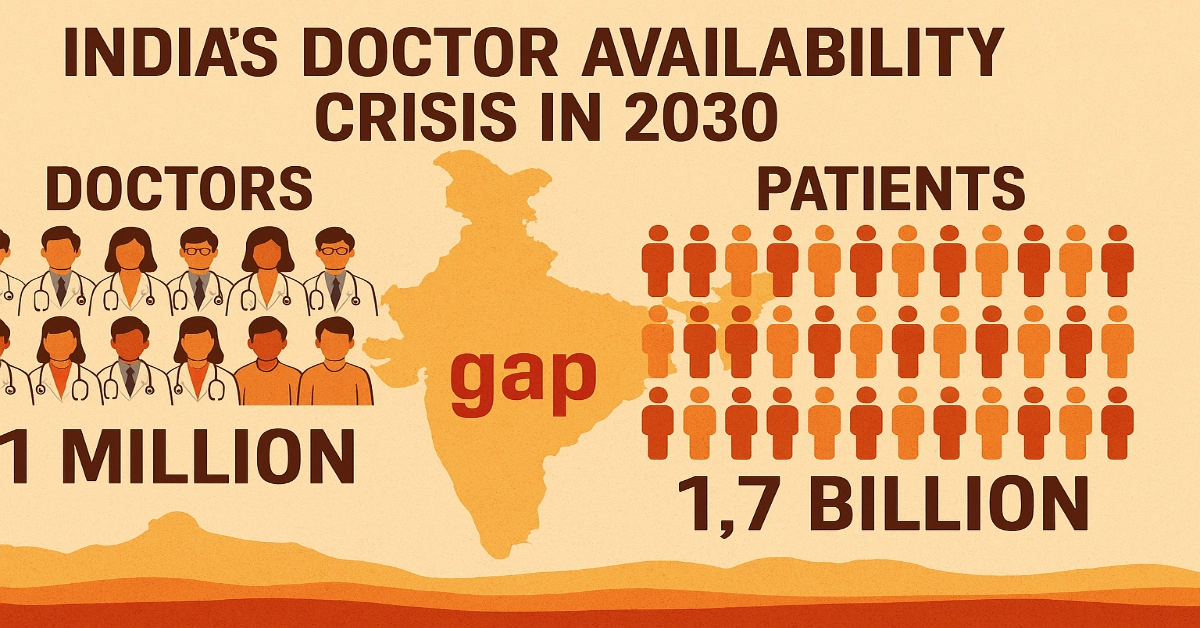

Projections for 2020 and 2030: Will India Meet the Global Norm?

If India continues its historical trend of 45% decadal growth in registered doctors:

Table 6: Projected Registered Doctor Stock

| Year | Projected Stock |

|---|---|

| 2030 | 17,33,873 |

Table 7: Projected Active Doctors (After Retirement + Emigration)

| Year | Active Doctors | Doctor-Population Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 2030 | 10,18,008 | 6.9 per 10,000 |

Even by 2030, India will not reach the WHO-recommended ratio of 1 doctor per 1,000 people (i.e., 10 per 10,000).

To Meet the 1:1000 Ratio by 2030

India would need:

- 15,00,000 active doctors

- 20,00,000 registered doctors (after accounting for retirement + emigration)

This requires 80% growth in registered doctors from 2024 to 2030, a nearly impossible target.

Read Also: How Many Doctors India Needs in 2030? WHO vs NMC Projection Model

Rural India: The Epicentre of the Crisis

The shortage of doctors is worst in rural and tribal regions.

Why Doctors Avoid Rural Service

- Lack of infrastructure

- Limited diagnostic tools

- Poor working conditions

- Lower earning potential

- Safety issues

- Lack of educational facilities for children

- Minimal opportunities for career advancement

Rural postings become even less attractive for specialists, who prefer to work in tertiary hospitals or private corporate chains.

Consequences

- High maternal and infant mortality

- Low institutional delivery rates

- Inadequate management of communicable and non-communicable diseases

- Overburdened primary health centers

- Excessive dependence on informal or unqualified practitioners

Policy Recommendations: What India Must Do for 2030 and Beyond

To bridge the doctor gap and improve health outcomes, India needs a multi-pronged strategy.

1. Establish a Separate Rural Health Cadre

A dedicated cadre of community-based practitioners with:

- Shorter medical training (3-4 years)

- Mandatory service in rural areas

- Training focused on primary care, public health, and emergency care

2. Strengthen Government Medical Colleges

Instead of relying excessively on private institutions, India must:

- Expand government colleges

- Improve faculty quality

- Invest in teaching hospitals

- Provide subsidized medical education to deserving candidates

3. Rationalize Medical Specialization

Encourage more graduates to pursue:

- Family medicine

- Community health

- General practice

These are the specialties India needs the most.

4. Create Incentives for Rural Service

Including:

- Higher salaries

- Housing allowances

- Risk allowances

- Guaranteed postgraduate seats after rural service

5. Curb Brain Drain Strategically

Possible approaches:

- Bonding systems

- Attractive career opportunities

- Exchange programs with Western countries

- Upgrading medical infrastructure in India

6. Improve Primary Healthcare Infrastructure

Doctors cannot be effective without:

- Laboratories

- Medicines

- Ambulances

- Trained nurses

- Skilled health personnel

India must follow the Sri Lankan model of highly functional primary health centers.

Read Also: Decolonising Medical Education in India: Independence Day 2025

India Needs More Than Just More Doctors

India’s failure to achieve strong health outcomes is not just due to a numerical shortage of doctors. The deeper problem lies in:

- Poor distribution

- Mismatched training

- Inaccurate workforce data

- High emigration

- Weak primary care infrastructure

- Limited rural access

Allopathic Doctors Registered With State Medical Councils (India)

Source: National Medical Commission

| Sl. No. | State Medical Council | Total Allopathic Doctors |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andhra Pradesh Medical Council | 105,799 |

| 2 | Arunachal Pradesh Medical Council | 1,461 |

| 3 | Assam Medical Council | 25,561 |

| 4 | Bihar Medical Council | 48,192 |

| 5 | Chhattisgarh Medical Council | 10,020 |

| 6 | Delhi Medical Council | 30,817 |

| 7 | Goa Medical Council | 4,035 |

| 8 | Gujarat Medical Council | 72,406 |

| 9 | Haryana Medical Council | 15,687 |

| 10 | Himachal Pradesh Medical Council | 5,038 |

| 11 | Jammu & Kashmir Medical Council | 17,574 |

| 12 | Jharkhand Medical Council | 7,374 |

| 13 | Karnataka Medical Council | 134,426 |

| 14 | Madhya Pradesh Medical Council | 42,596 |

| 15 | Maharashtra Medical Council | 188,545 |

| 16 | Erstwhile Medical Council of India | 52,669 |

| 17 | Mizoram Medical Council | 156 |

| 18 | Nagaland Medical Council | 141 |

| 19 | Orissa Council of Medical Registration | 26,924 |

| 20 | Punjab Medical Council | 51,689 |

| 21 | Rajasthan Medical Council | 48,232 |

| 22 | Sikkim Medical Council | 1,501 |

| 23 | Tamil Nadu Medical Council | 148,217 |

| 24 | Travancore Medical Council | 72,999 |

| 25 | Uttar Pradesh Medical Council | 89,287 |

| 26 | Uttaranchal Medical Council | 10,243 |

| 27 | West Bengal Medical Council | 78,740 |

| 28 | Tripura Medical Council | 2,681 |

| 29 | Telangana Medical Council | 14,999 |

| — | Grand Total | 1,308,009 |

Simply producing more MBBS doctors will not solve the crisis. India must focus on creating a balanced, motivated, well-distributed, and efficiently utilized health workforce.

If India continues current trends, the country will reach only 6.9 doctors per 10,000 people by 2030, far below global standards.

A transformative, long-term approach, grounded in structural reform, rural health investment, and workforce planning, is urgently needed for India to truly achieve “Health for All”.