Recent controversy related to medical education after CBI exposed medical college inspection fraud has restarted debate on India’s federal structure in healthcare and education ignited by Tamil Nadu Report by recommending that states be given greater autonomy.

The report, submitted to a high-level committee on Centre-State relations in Tamil Nadu, argues that the “unitary approach adopted by the Union government” has eroded the constitutional space for states in health and medical education, undermining efficiency and social justice.

Tamil Nadu’s demand comes against the backdrop of its strong public health track record and history of resisting central impositions such as the NEET exam.

This article explores the report’s recommendations, the policy implications, the historical context of Centre, State power sharing, comparisons with other states, and the constitutional framework shaping this debate.

Key Recommendations of the Tamil Nadu Report

The report makes a strong case for restoring state powers in health and medical education. Its major recommendations include:

Returning Medical Education to the State List

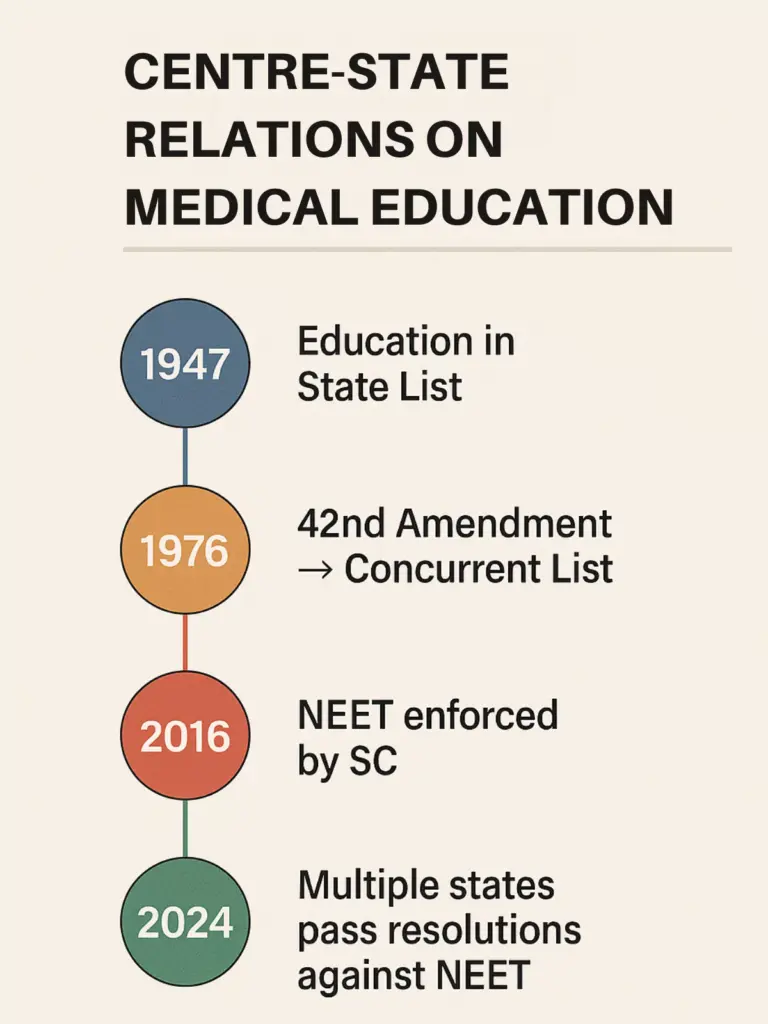

- The 42nd Constitutional Amendment (1976) shifted education from the State List to the Concurrent List.

- Tamil Nadu argues this created a disconnect: health is a state subject, but medical education is centrally controlled.

- Restoring medical education to the State List would allow state-level curricula, admissions, and training systems aligned with local needs.

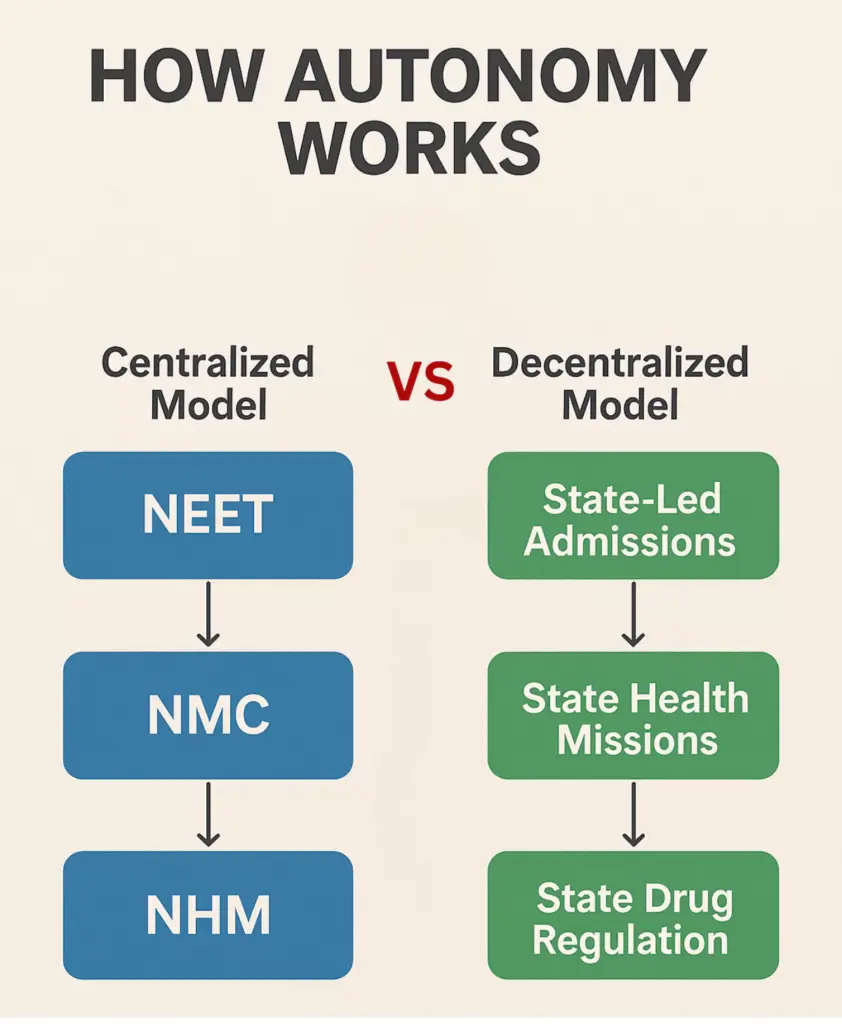

Reforming the National Medical Commission (NMC)

- Tamil Nadu seeks more state input in medical policy, and alternatives to NEET and NEXT, which it says disadvantage rural and non-English medium students.

- The National Medical Commission (NMC) is criticized as functioning like a sub-unit of the Union Health Ministry, with minimal state representation.

Decentralising National Health Programs

- Schemes like the National Health Mission (NHM) are seen as overly centralised.

- Tamil Nadu proposes states should set health priorities, targets, and fund flow mechanisms, with financial support from the Centre.

Empowering State Drug Regulators

- The Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) dominates drug regulation.

- Tamil Nadu wants stronger state-level regulators to respond to local needs, curb spurious drugs, and support small manufacturers.

Protecting State-Led Healthcare Models

- Tamil Nadu’s cadaver organ transplant program is world-renowned.

- The Union’s move to centralise organ donation under National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO) could dilute state successes.

- The report stresses that proven state models should operate autonomously.

Avoiding One-Size-Fits-All Policies

- Tamil Nadu insists that local languages, contexts, and scientific priorities must guide health and education policy.

- Imposing AYUSH integration into MBBS and branding schemes in Hindi are seen as cultural impositions.

Over-centralisation, the report notes, has “slowed down responses to local disease patterns and created barriers for smaller manufacturers.”

Read Also: India’s Medical Education Revolution: NMC Reforms, CBME, NEXT & More

Health Outcomes: Tamil Nadu vs. India

Tamil Nadu’s demand gains weight when compared with national averages.

| Indicator | Tamil Nadu | National Average | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant Mortality Rate (per 1,000 live births) | 18 | 35 | NFHS-5 / MoHFW |

| Maternal Mortality Ratio (per 100,000 live births) | 60 | 113 | SRS 2020 |

| Institutional Deliveries (%) | 99% | 79% | NFHS-5 |

| Life Expectancy (years) | 72 | 69 | NITI Aayog |

These figures highlight Tamil Nadu’s superior public health achievements, often credited to state-driven innovations.

Policy Implications: Benefits and Challenges

Potential Benefits

- Tailored Solutions: States can adapt policies to local disease burdens. Tamil Nadu’s achievements, IMR of 18, MMR of 60, and 99% institutional deliveries, show the value of state-driven innovation.

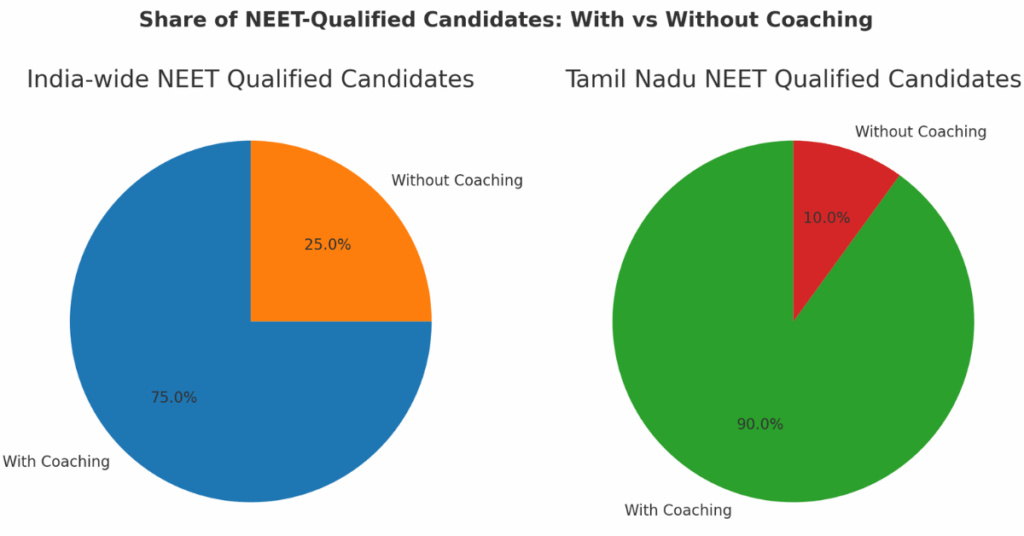

- Social Justice: Tamil Nadu’s earlier admissions system (based on school marks) increased intake of rural and first-generation students, unlike NEET which favors urban, wealthy students.

- Innovation & Competitive Federalism: States could experiment and replicate each other’s successes, like Tamil Nadu’s organ transplant program or Kerala’s community health models.

- Strengthening Federalism: Greater autonomy would reaffirm India’s cooperative federal structure, aligning decision-making with the principle of subsidiarity.

Key Challenges

- National Standards: Central oversight helps ensure uniform medical standards. Without NEET or NMC, disparities could emerge in doctor quality across states.

- Inequality Across States: Wealthier states may thrive with autonomy, but weaker states could fall further behind without central guidance and funding.

- Pandemic Response: National crises like COVID-19 showed the need for unified strategies. Excessive decentralization might hinder coordination.

- Constitutional Hurdles: Undoing the 42nd Amendment requires a two-thirds majority in Parliament and ratification by states, politically challenging.

- Student Mobility: Multiple state exams could fragment opportunities and increase barriers for students seeking admission outside their home states.

Historical Context: How Power Shifted

At independence, public health and education were both State List subjects. States controlled medical admissions, curricula, and public health programs.

In 1976, the 42nd Amendment moved education to the Concurrent List, giving the Centre more power. This paved the way for bodies like the Medical Council of India (MCI) and later the NMC.

The introduction of NEET in 2016, upheld by the Supreme Court, was the most significant centralizing step, replacing diverse state-level entrance exams. Tamil Nadu had abolished its own medical entrance test in 2006, relying on school marks, an approach it credits with democratizing access.

Tamil Nadu’s resistance is rooted in its Dravidian political movement, which has historically emphasized social justice and state autonomy.

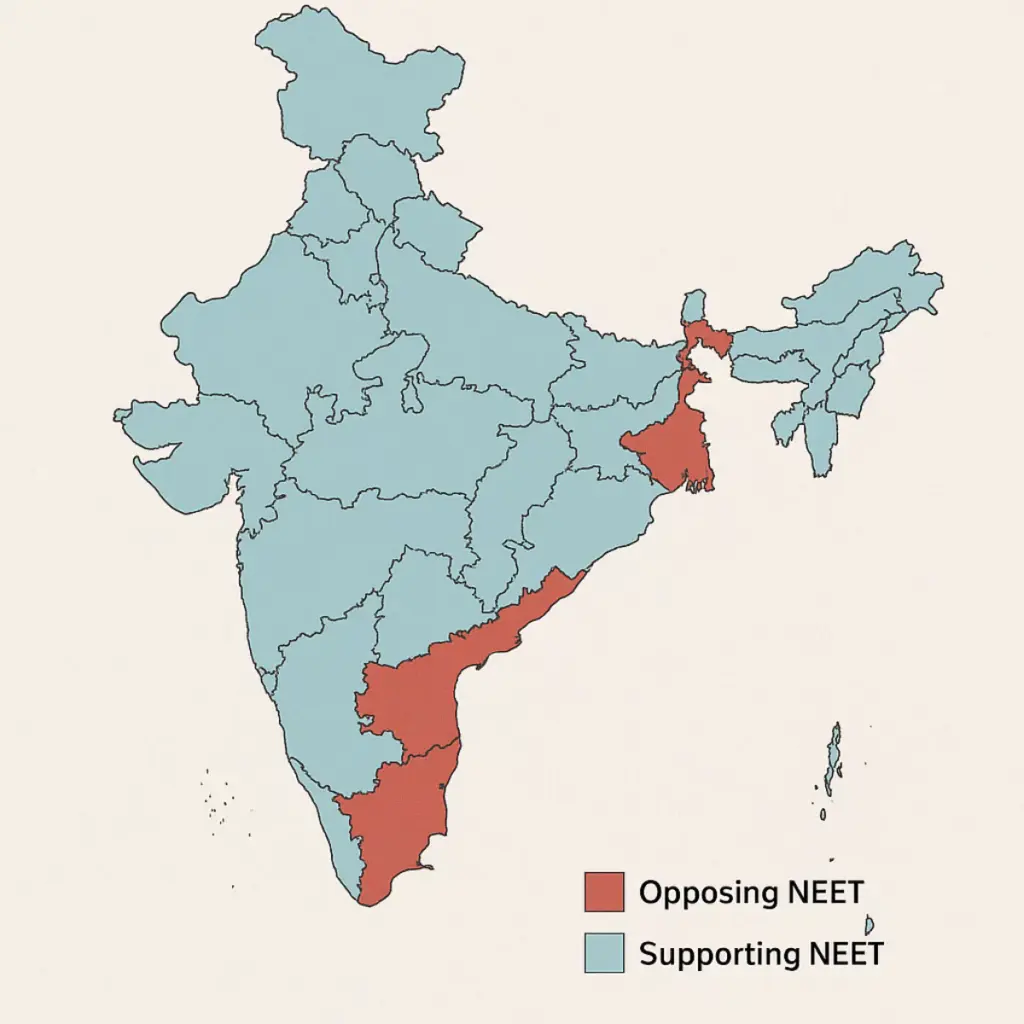

Comparative Analysis: Other States’ Positions

- West Bengal opted out of Ayushman Bharat and recently resolved to scrap NEET, citing exam irregularities.

- Karnataka approved a resolution to replace NEET with a state-level exam, arguing state students were disadvantaged.

- Odisha and Delhi have run their own health insurance schemes instead of adopting central ones.

- On the other hand, states like Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh, and Gujarat have welcomed central schemes for uniformity and transparency.

This shows a divide: states with strong regional identities and robust health systems push for autonomy, while others prefer the stability and funding of central schemes.

Constitutional Framework

- State List (Entry 6, List II): Public health and hospitals are under state control.

- Concurrent List (Entry 25, List III): Education, including medical education, is shared, but Union laws prevail.

- Union List (Entry 66, List I): The Centre controls “coordination and determination of standards.”

- Article 254(2): Allows states to pass laws in concurrent subjects if approved by the President. Tamil Nadu’s anti-NEET bills have stalled at this stage.

- Constitutional Amendment: Needed to restore education fully to the State List.

Move to Cooperative Federalism

Tamil Nadu’s case highlights a larger national question: Should India centralize for uniformity, or decentralize for diversity?

Tamil Nadu’s report is not just about Centre vs. State conflict, but about reimagining India’s federal balance in healthcare and education.

- Restoring state autonomy could enable equitable admissions, localised health solutions, and innovative state models.

- But risks include fragmentation, unequal outcomes, and legal hurdles.

- A cooperative federalism approach, where the Centre ensures minimum national standards and funding, while states retain flexibility, appears the most pragmatic path forward.

The Tamil Nadu report has opened a critical debate on India’s federalism in health and education. With its strong health outcomes and social justice legacy, Tamil Nadu makes a compelling case for decentralisation. However, ensuring quality, equity, and coordination across states remains a national priority.

For policymakers, students, and healthcare professionals, the big question is: Should India decentralise for diversity, or centralise for uniformity?

The answer may lie in a balanced model of cooperative federalism that empowers states while safeguarding national interests.