“When medical colleges become businesses and monopolies, students become customers, and healthcare becomes a commodity. And, healthcare is right, not commodities.”

Monopoly in Medical Education in India: India’s medical education system is often described as rapidly expanding, with the emergence of new colleges, increasing seat numbers, and an ongoing promise of more doctors to meet the needs of a growing population. Yet in reality lies a different story: ownership concentration, financial gatekeeping, and structural incentives that create de facto monopoly in medical education in India.

This article examines how concentrated ownership and weakly scrutinised and policed market power shape access, quality and the real cost of medical education in India today.

| “Even today, children, mostly belonging to the middle class, are going abroad for medical education. They spend lakhs and crores on medical education abroad. Around 25,000 youths every year go abroad for medical education and they go to such countries, I get surprised when I hear about them. So we have decided, 75,000 new seats will be created in the medical line in the next five years.” – Sri Narendra Modi, PM of India, at 2024 Independence Speech |

India’s Rapidly Expanding Medical Education Landscape

MBBS Seats Surge but Monopoly Persists

Few years back India took over USA and UK combined in MBBS seat expansion, but it lacks the requisite infrastructure and other requirements. And moreover, India has less far more colleges but produce less doctor than china.

India is currently facing accute faculty crisis in medical colleges, government and private alike.

Official data show a continuing rise in the country’s MBBS capacity. The National Medical Commission’s (NMC) recent seat matrix puts the total MBBS seats in India in the order of 120-124 thousand after several rounds of approvals for new seats.

But a raw data hides two important realities.

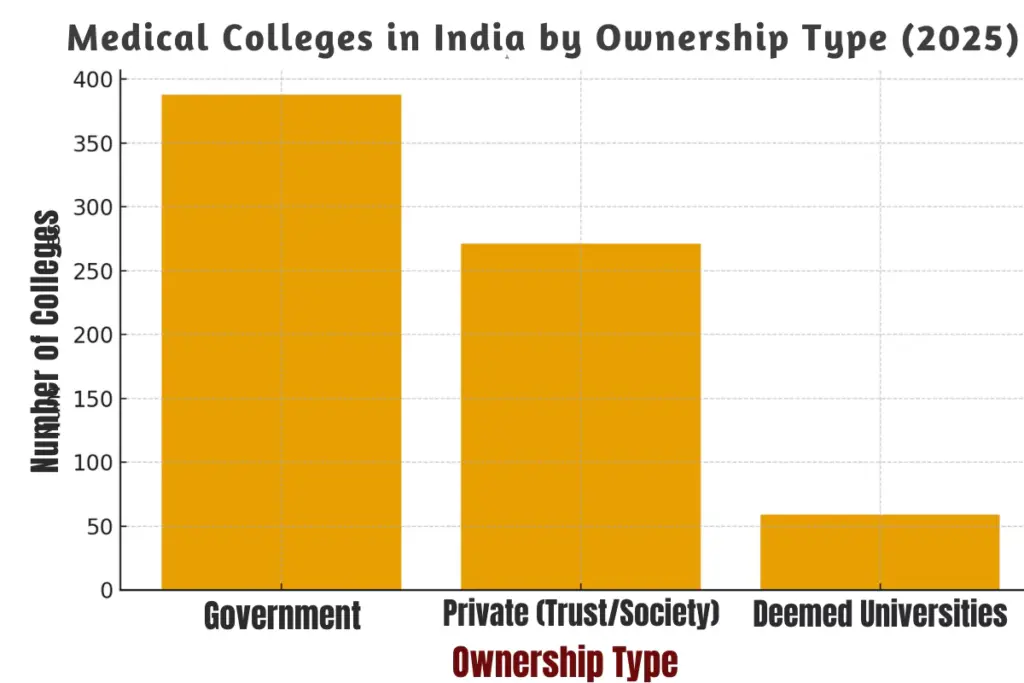

Private Medical Colleges Outpace Government Colleges

First: a large share of these seats is now in privately owned colleges. Second: while the quantity of seats has grown, ownership is increasingly concentrated in a relatively small number of trusts, educational groups and hospital chains, especially in certain states.

The combination of lots of private seats plus concentrated ownership creates the conditions in which market power can grow.

Read Also: Medical Education in India 2025: MBBS Seat Expansion, AI Integration, and Fee Trends Explained

Monopoly in Medical Education: Who Really Owns India’s Medical Colleges?

“A monopoly in medical education isn’t just about ownership; it’s about who cannot afford to dream.”

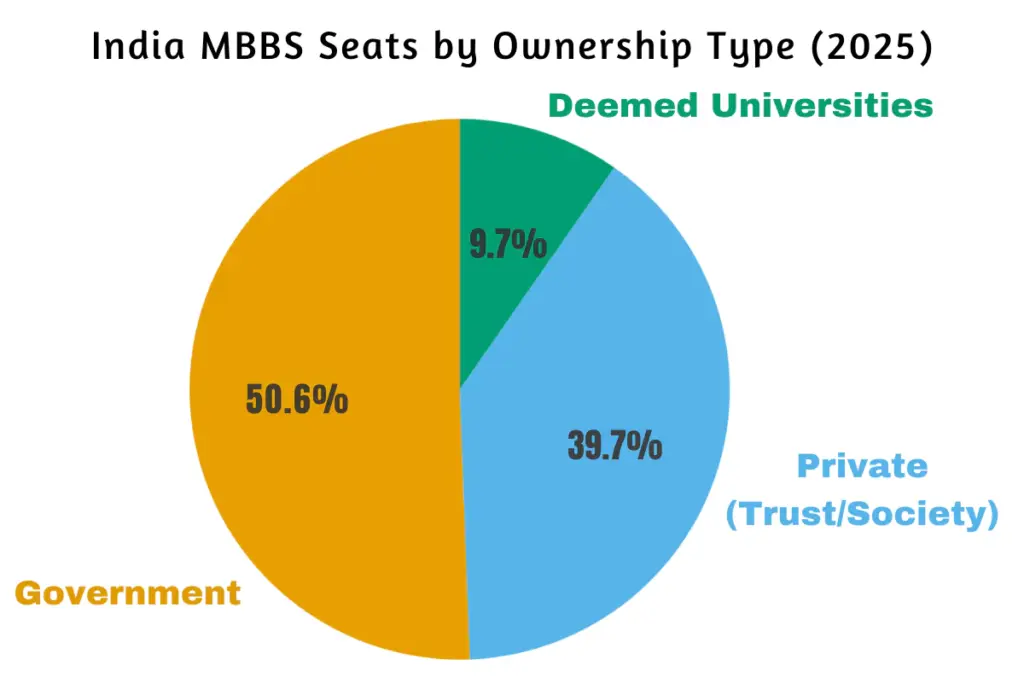

While the number of MBBS seats has doubled over the past decade, ownership concentration remains. The chart below shows how the country’s MBBS capacity is split between government institutions, private trusts, and deemed universities. This concentration directly affects affordability, regulation, and the student experience.

Ownership Breakdown 2025 (Government vs. Private Trust vs. Deemed Universities)

Even though the total number of MBBS seats in India has crossed 1,18,000 in 2025, the ownership pattern shows a clear dominance of private trusts and societies.

Despite public perception, government colleges make up just over half of all MBBS seats. Private trusts and deemed universities together control the rest, a pattern that strengthens their market power and pricing leverage.

How Monopoly Appears in Medical Education

“Ownership concentration in medical colleges may yield profits, but the price is paid by students and patients.”

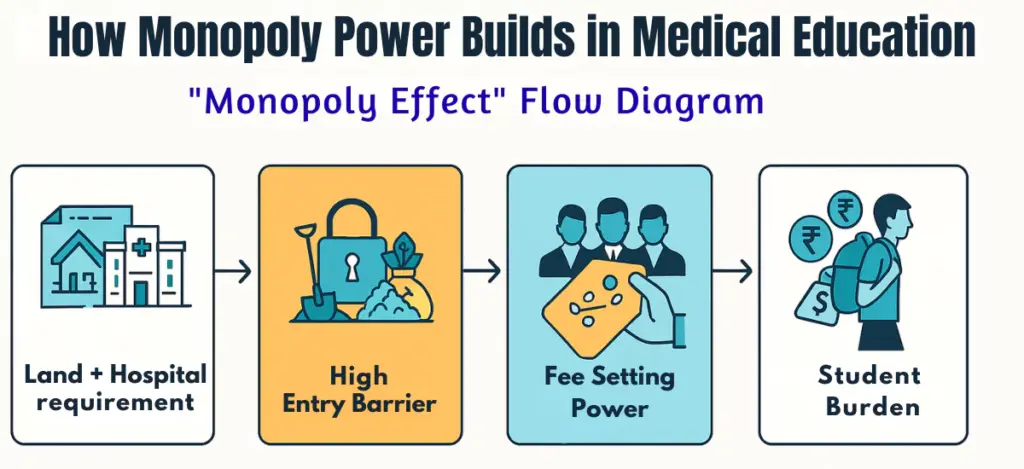

Monopoly or oligopoly behaviour in medical education shows up in four connected ways:

Pricing power and fee structures

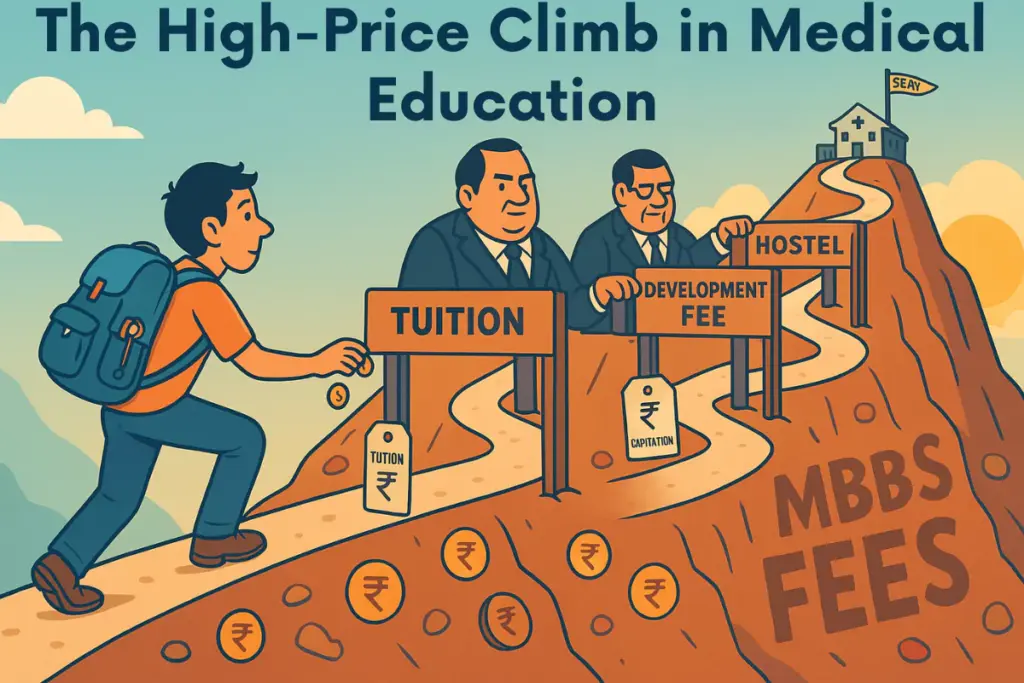

Private medical college fees for MBBS are significantly higher than government college fees, and for many colleges, they are not set purely by competitive market forces. Even with NEET as a common entrance test, management quotas, NRI quotas and differential fee slabs mean the effective price faced by aspirants varies widely. Regulatory attempts to cap or standardise fees have been partial and contested.

Barriers to entry

Starting a medical college and increasing MBBS seats in India requires large land parcels, a teaching hospital of specified bed strength, specialist faculty and repeated regulatory inspections. These high fixed costs favour large education groups and institutional owners who can invest at scale, not small players. The result: fewer, bigger owners rather than many small, competing providers.

Control over seat allocation channels

While NEET provides a merit-based central entrance, admissions also involve state-level counselling, management quotas and institutional seats. These channels can be used to preserve higher fee blocks and gatekeep access for those without deep pockets.

Regulatory influence and capture

Owners of large hospital-college complexes often have political connections or the resources to navigate state-level approvals, acquisitions and renewals. This asymmetry can weaken regulatory discipline and slow reforms that would increase competition in meaningful ways.

Read Also: Education and Healthcare Now a Business in India- Mohan Bhagwat

Real effects on students and public health

The concentration of ownership and the resulting market power have consequences that ripple far beyond balance sheets.

Affordability and social mobility

High fees, especially for management and NRI seats, restrict access for meritorious but economically weaker aspirants.

The existence of legally proscribed practices (like capitation fees) in the past, and the persistence of work-arounds today (variegated fee schedules, ‘development charges’, donation routes), means financial background still matters.

The Supreme Court of India has repeatedly condemned capitation fees, but enforcement problems remain.

Quality and incentives

When ownership is profit-oriented and seats are a major revenue line, there’s a danger of prioritising quantity over quality, cutting faculty hires, compressing clinical exposure, or outsourcing key services.

Conversely, a few reputable private institutions have invested in quality and research; the point is that concentration can produce uneven quality outcomes that hinge on owner choices rather than standard competitive pressures.

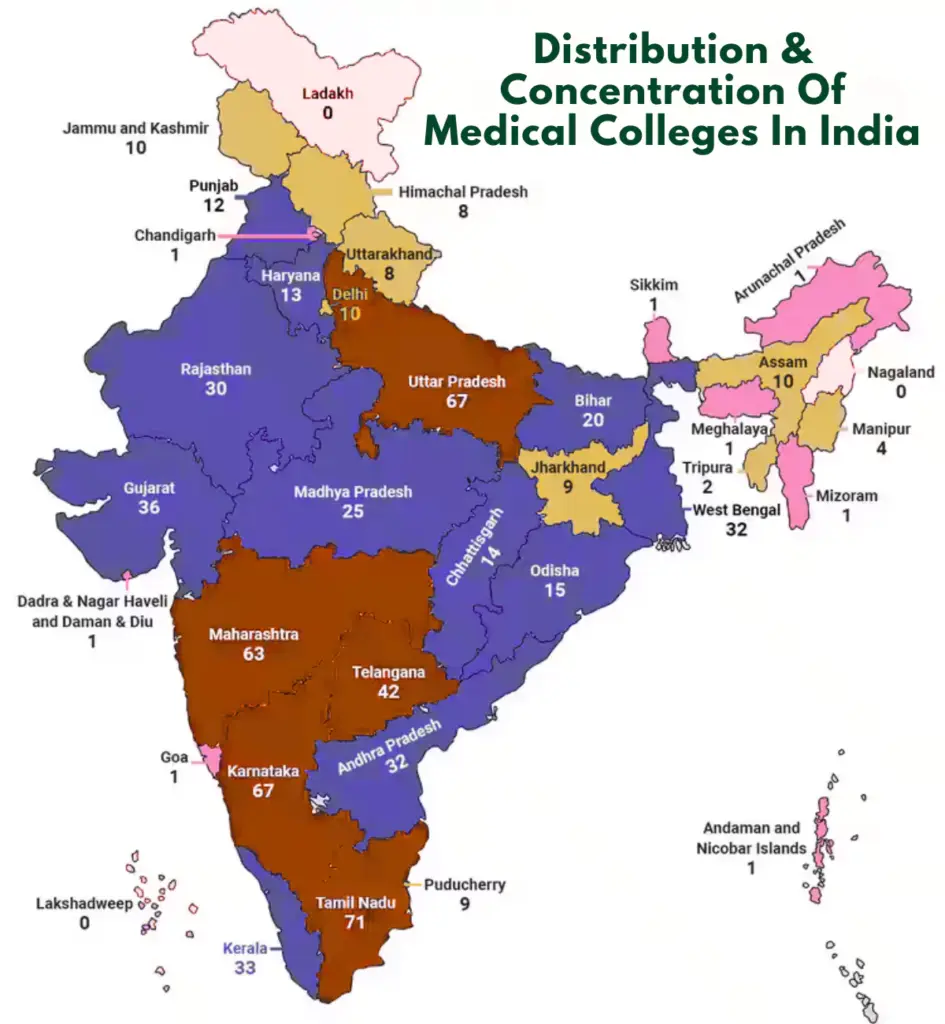

Geographic maldistribution

Private colleges tend to cluster where land, paying demand and political economy favour investment, often in southern and western states.

Underserved regions, therefore, continue to lack medical training capacity, worsening local shortages of doctors and making healthcare inequities more persistent.

Misaligned supply for national health needs

A monopolised market driven by returns can bias supply toward high-fee specialities, electives that are revenue-generating, or urban hospital attachments, not necessarily toward rural health, primary care, or public-health priorities.

Case Studies and Patterns in Private Medical College Expansion

India’s private medical education sector isn’t monolithic; it’s shaped by regional political economies, legacy trusts, and regulatory dynamics. Examining specific states and policy moves reveals how ownership concentration forms, and how it’s being contested.

Southern States as Microcosms of Ownership Concentration

Southern India, particularly Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala, offers a classic case study of concentrated ownership in medical education.

Long-standing educational trusts and hospital chains

Many of the oldest private medical colleges in these states were set up by large educational societies or religious/charitable trusts with deep financial and political networks.

Over time, these trusts diversified, creating vertically integrated ecosystems of schools, colleges, and tertiary-care hospitals.

Economies of scale and brand leverage

These groups typically own multiple institutions under the same umbrella. For instance, one hospital may serve as the teaching facility for two or three affiliated colleges.

This allows them to spread fixed costs across multiple entities, negotiate better financing, and exert influence over seat allocations at the state level.

State-level regulatory and political climate

Southern states historically allowed more liberal private-sector participation in higher education, combined with a strong demand for healthcare services. This made them attractive to investors and charitable trusts alike.

Today, Karnataka alone accounts for one of the largest blocks of private MBBS seats in India.

Together, these factors make the southern region a microcosm of how private capital, high fixed costs, and regulatory leniency converge to create concentrated ownership and, by extension, market power.

National Medical Commission’s Fee Transparency Push

“Expanding medical seats without regulating fees is like building gates without unlocking the doors.”

Recognising the risks of concentrated pricing power, the National Medical Commission (NMC) has attempted to introduce fee transparency and partial fee-regulation measures for private colleges.

NMC Key Guidelines

In 2022, the NMC issued a directive that 50% of seats in private medical colleges and deemed universities should be charged at the same level as government medical colleges in the same state. This was intended to standardise costs for at least a portion of seats.

Resistance and legal challenges

Implementation has been uneven. Several private institutions have challenged the directive in court, arguing it undermines their financial sustainability and autonomy. Some states have delayed or diluted enforcement, citing administrative difficulties.

Transparency on paper vs. ground reality

Even where the rule is in effect, multiple fee layers, such as “development charges,” “donations,” or mandatory hostel and service fees, can blunt its impact. Students and parents report substantial variation between the advertised fee and the total cost of admission.

Potential upside

If enforced strictly, NMC’s transparency drive could chip away at monopoly pricing and give economically weaker students a foothold. It would also generate more reliable comparative data for policymakers, media, and civil society to monitor affordability trends.

Why Monopoly in Medical Education Persists?

From a market-structure view, several economic features explain why medical education is prone to concentration:

- High fixed costs and scale economies. Building a teaching hospital and meeting regulatory infrastructure norms creates scale advantages.

- Regulatory complexity. Frequent inspections, renewals, and approvals favour organisations with legal and bureaucratic bandwidth.

- Revenue complementarities. Colleges linked with large hospitals can cross-subsidise education from clinical service income, making them more resilient and capable of growing capacity.

- Information asymmetry. Prospective students and parents find it hard to compare long-term educational quality; reputation and brand therefore matter more than pure price competition.

All these factors limit potential entrants and embolden large players.

Read Also: India’s Medical Education Revolution: NMC Reforms, CBME, NEXT & More

Regulation, Remedies and their Limits

Several regulatory levers exist, and some have been tried, but each faces limits.

Fee regulation and transparency

The National Medical Commission (NMC) has proposed and, in some cases, implemented rules to regulate fees (for example, guidelines that subject a portion of private seats to government-level fee limits). Fee regulation can protect students, but it requires robust, granular audits and legal backing to avoid circumvention.

Increasing public supply

Building more government medical colleges in underserved regions directly combats private concentration and expands lower-fee, accessible seats. The challenge: public investment, operating budgets and faculty recruitment are real constraints for governments.

Stronger accreditation and outcome-based oversight

Linking renewal and seat approval to measurable education outcomes, graduate pass rates, clinical exposure benchmarks, research output, patient volumes, could discipline owners. But regulators need both capacity and independence to apply these metrics fairly.

Limit entry conditions tied to public obligations

A possible policy lever is to allow private entrants only under conditions that protect public interest: fixed quotas for economically weaker students, rural-service bonds, transparent endowments for faculty development, or caps on related-party expansions. Enforcement and political will are the tough parts.

Breaking the Monopoly in Medical Education: Reform Package

Practical, politically feasible reform should combine supply-side and demand-side measures:

- Accelerated public investment in medical colleges targeted at underserved states and districts (reduce geographic concentration).

- Transparent, audited fee scaffolds for private colleges with severe penalties for hidden donations or misreporting. The NMC’s steps toward fee transparency are a start but must be enforced uniformly.

- Outcome-linked approvals: seat increases or new colleges granted only when educational outcomes meet defined benchmarks over a probationary period.

- Stronger consumer information: an accessible national dashboard that compares colleges on fees, pass rates, faculty strength and clinical exposure.

- Encouraging alternative providers: public-private partnership models where the private partner invests but the contract specifies public-interest outputs (rural service, low-fee seats, scholarship commitments).

Price, Power and the Social Compact

India’s rapid expansion of MBBS seats has been celebrated as a milestone in health capacity-building. But when ownership and pricing power concentrate in a few hands, the social contract behind medical education, that it should train enough doctors for all citizens and reflect merit over money, begins to fray.

Why Monopoly Threatens the Goal of Universal Health Access

Monopolistic or oligopolistic control over medical education raises barriers for talented but less affluent students. High tuition and management quotas channel opportunity toward the wealthy, reinforcing inequality.

Downstream, this limits the supply of doctors willing to work in underserved areas, as graduates saddled with high debt prefer lucrative urban specialities.

Ultimately, the health system suffers because the doctor-to-patient ratio remains skewed and rural or public-health roles go unfilled.

Also Read: History of Medical Education in India: Ancient to Modern Reforms

A Multi-Pronged Strategy to Balance Access, Quality and Cost

Breaking monopoly power is not about dismantling private participation but about reshaping incentives:

- Expand Public Colleges in underserved states and districts to dilute private dominance.

- Tie Private Expansion to Public Outcomes such as rural-service obligations, fee-capped seats or scholarship quotas.

- Outcome-Based Accreditation linking seat approvals to teaching quality, clinical exposure and pass rates.

- Transparency & Consumer Dashboards allowing students to compare fees, infrastructure and outcomes across institutions.

Together, these measures broaden access, keep prices in check and create competitive pressure for quality improvements.

Policy Recommendations for 2025 and Beyond

- Enforce Fee Caps on Half of Private Seats with real-time auditing of “hidden charges.”

- Introduce a National Medical Education Portal listing college-wise fees, faculty-student ratios, pass rates, clinical volumes and grievance channels.

- Offer Incentives for Rural Medical Colleges, land grants, interest subsidies, faculty fellowships, to spread training capacity beyond current clusters.

- Legal Safeguards on Ownership Concentration (for example, limits on how many medical colleges one trust can own in a state without public-interest obligations).

- Long-Term Public Investment in new government teaching hospitals with modern facilities and bonded service programs to anchor public health needs.

These steps don’t remove private colleges from the ecosystem; they aim to restore balance so that price, power and policy serve the public good rather than entrench monopoly advantage.

Medical education is in shambles in India. On one hand no of medical colleges and seats are increasing in phenomenal manner,the two crucial social issues are lagging behind further. One due to dominance of private players ,the affordability for an economically weaker but meritorious students is drastically turning decimal, secondly under the private players government is every year reducing percentile for admission,as a result mediocre but wealthy students are capturing seats in medical colleges. Poor infrastructures in these medical shoppe coupled with shortage of trained and dedicated faculty has led to generation of mediocre and poorly trained doctors. This has put the quality of entire health care delivery system in India to a very pathetic pedestal. The ultimate victims are patients who are and will get poor quality health care at high price.Goverment needs to do a surgical strike.However it requires strong political will,as stakes are very high due to deep penetration of political patronage in medical education. Government should encourage more state owned medical college ,should take over medical colleges with poor infrastructures and if at all private players need to be in pool,then only not-for-profit organisations should be given permission to run medical colleges.Otherwise in coming decade India will be flooded with incompetent, unskilled doctors and corporate hospitals,with sole objectives of profits only at the cost of patients life and savings. There is urgent need for radical reform in medical education and health care system of India.National medical commission(NMC) which replaced old corruption bound Medical Council of India(MCI) couldn’t bring any positive changes in medical education rather is catalysing rapid deterioration . Only GOD can help.patients and society at large.